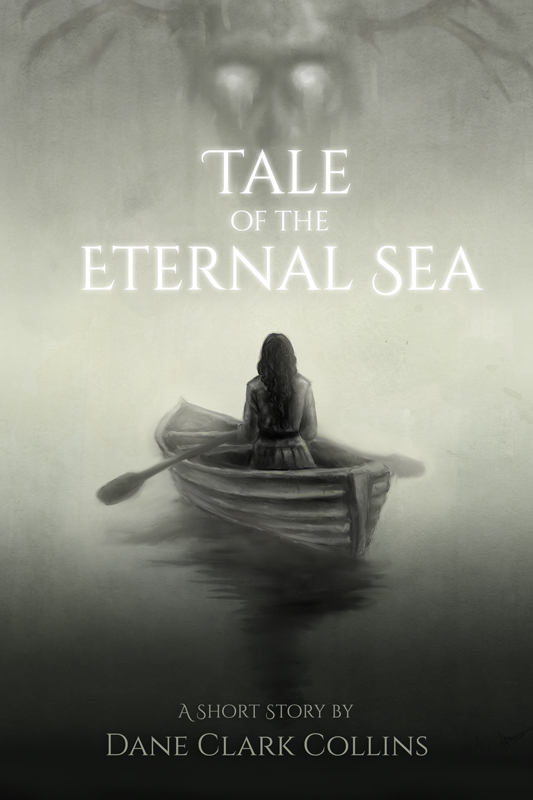

A mythic adventure on an endless sea. A surreal horror about the search for eternal life.

After a shipwreck strands six survivors in a small, battered boat, they drift through a boundless, silent ocean where time and reality blur. Haunted by strange visions, secrets, and a feeling of being watched, each is driven by a mix of desperation and distrust. The oppressive silence is broken only by the whispers of unseen entities lurking beneath the waves. As hunger gnaws and hope fades, they stumble upon an eerie, isolated island shrouded in mist and must confront the darkness lurking within themselves.

As the journey continues, the young girl at the center of the story is drawn deeper into a surreal world of ancient myths and primal forces, where nature holds secrets more terrifying than death itself. The line between reality and illusion grows thin, and the price of survival may be more than she bargained for.

This story has a soundtrack. It will have its own release soon, but for now, you can hear two of the songs on the Frightful Refrains compilation album.

Or read a sample…

Chapter I

I look down at my reflection in the water just before it scatters into thousands of pieces as the cracked oar splashes through it.

I look at the other five survivors. They all seem lost in thought. Or we’re growing despondent from malnutrition. The boat is damaged around the bow gunwale, but the damage is above the water, so we’ve stayed dry and afloat. The adults take turns rowing—at least, that’s the idea. Roddy has insisted on rowing for the past several hours and seems intent on continuing.

My father makes a sound in his throat, breaking the silence. “Has anyone ever seen water this still on the open sea?” No one answers, but I see the fear in their eyes. This isn’t normal.

Roddy stops rowing and glares at my father. “What was it you said, Professor?” I can hear the contempt in his trembling voice. He wants to yell, but the eerie silence of the sea has made us all wary of making too much noise, so it comes out in a whisper. When my father doesn’t answer, Roddy kicks him in the shin with the heel of his boot. “Come on, mapmaker, what was it? What did you say?”

“I told you I teach cartography. I never said I was a mapmaker.” My father is neither a cartography teacher nor a mapmaker, but I say nothing.

“If you can teach it, you should be able to do it.”

“I can. You misunderstand me. I wasn’t wrong about the direction.”

“I don’t care. Just answer my question. What did you say?”

“I don’t know what you want me to tell you.”

“I’ll remind you, then. You said that if we kept that star on our port side and never changed course, we would find land.”

“Yes. It’s the only way I know to stay oriented. That star is the only consistently visible frame of reference in this fog. Keep it to our port side, and we’ll reach land. But without knowing our speed or distance, I can’t guess how long it will take.”

“Maybe there was land closer in another direction.”

“You had no better ideas. This was our best chance.”

“What chance? Where the fuck is the land?”

“What choice do we have now? We keep going.”

“Maybe our bearing was off, and we missed it. The land you claim exists could be well behind us by now.”

“We have to maintain this bearing. We’re still in the fog. We can’t change course now.” There was growing desperation in my father’s voice.

Roddy stopped rowing and stared into my father’s eyes for some time. “Why are you so determined, and what does this fog have to do with our direction?”

“Please, Roddy. Just keep going.”

“You know what I think, Professor? I think you’ve lied to us, and I think you’ve gotten us all killed.”

“Again, no one else was offering any ideas. Our food was at the bottom of the ocean. What would you have done differently?”

Roddy says nothing, but I see hatred in his glare.

“What would you have us do now, then?”

“I’d turn this boat around and do the opposite of what you’ve told us.”

“Two days, Roddy. We’ve rowed for two days, and—“

“Days? What days? The sky lightened, but we could still see that damn star. Where was the sun?”

“It’s this fog, Roddy. Listen to me. We’ve come all this way, and you want to turn around and spend another two days getting back to where we started? We have no food or water.”

“We could always eat the first to die, and I can make sure that’s the person who got us lost.”

Terry, sitting directly across from me, interrupts. “Please shut up, Roddy. This is difficult enough without you starting fights.” Terry has large eyes that look like they could fall out of their sockets with the smallest pressure, and his frustration is creating pressure.

“We’re going to die, Terry, if we don’t find land soon. You understand that, don’t you?”

“Of course, I understand that,” he roars. “So we keep pushing forward.”

“For how much longer?” Roddy looks around the boat, and all eyes are on him. “Are all of you on this liar’s side?”

“It’s not about sides,” says Terry. “What’s our alternative? We turn around, row the other way? And in a couple of days, maybe our corpses will drift back to where the ship sank.”

“We could row straight toward the star. Or away from it. Going back isn’t the only other option.”

“No matter where you are, if you move in a set direction long enough, you’ll eventually run into land. If we go zigging and zagging now, we may never see land again.”

Roddy says nothing, but his eyes bore into Terry and my father in turn.

The silence is uncomfortable, so I look out across the sea. I can’t find the sun, but the sky casts a pale, fading blue on the fog. There are no birds. The air is still and warm.

“One of us can take over rowing for a while,” offers Agnes, sister to Terry’s wife, who went down with their ship. The three had bought passage on the whaler’s ship to see a new continent before they grew too old to travel.

“I think not,” Roddy growled.

Terry shakes his head, leans to his side, and stares across the sea. “It’s peaceful, isn’t it? Tranquil. Too tranquil for the ocean.”

“Damn it. This won’t do,” says Roddy. I hear a thump, and my father grunts and falls backward over the side of the boat. For a brief moment, my only concern is that we’ve disrupted the quiet of this placid sea. But then my father’s face breaks the surface. His eyes stare blankly at the sky while I stare blankly at him, not comprehending what has happened.

He shakes his head, and his eyes seem to find their focus. Blood runs down his forehead and face. He looks confused. He reaches up and grabs the boat to pull himself up, and the boat tips to the side, almost spilling us all into the water. The long board we’ve used as a paddle smashes into his head, and he slides back into the water.

The others in the boat start screaming. Terry and Virginia stretch their arms out to catch him, but they cannot reach him. He’s floating away from us. No, Roddy is rowing.

“Stop, Roddy.” Terry grabs one of the oars, and Roddy kicks him away. And just then, my father is pulled beneath the water.

Virginia slides backward and covers her mouth, eyes welling with tears. “Something got him. He didn’t just sink. He went down too fast. Something got him. Please, Roddy, we have to go back.”

“What are you going to do, Virginia?” Roddy asks. “Are you going to dive in after him?” Her lips move, but she seems unable to form a response. Her eyes flick to me, then downward, and she sits. Terry settles next to her. We all watch the spot where my father went down, but the water is still. After several minutes, the rowing resumes.

And it’s then that I finally scream. I lunge over the side of the boat toward where my father went down, and arms restrain me. Every muscle I have is straining toward the water. Their grip breaks, and I stumble forward. A hand clenched around my ankle. Another hooks around my waist. I tip forward, and my face submerges. I inhale water. Choking. I’m pulled back into the boat, and still, my muscles push until my entire body aches.

Terry looks at me with sad eyes. “It’s over, girl. There’s nothing for it now. Just sit, and we’ll see you safe back to land.” He doesn’t sound sure.

I feel their grips loosen and pull myself free, lunging for the oars, but Roddy kicks me across the face, and the others pin me back to the bottom of the boat until I’ve calmed.

I want to scream obscenities. I want to jump on Roddy and scratch until there’s no skin left on his face, and I want to dump him over the side to be eaten by the monsters below the surface. But I only stare. Terry’s arm pulls me back to my spot. The sudden quiet feels wrong, but I don’t break it. I want to cry, but tears won’t come.

That last sight of my father being pulled into the water repeats in my mind. Each time I relive it, I insist to myself, He’s not dead, but I’m not sure I believe it. I want to believe. Maybe he’s out there in the fog, waiting.

But I also know it’s useless. Even if we turned back now, or I managed to get into the water and swim, I’d never find him.

Terry stares coldly at Roddy. “That was murder.”

“So do something about it,” Roddy says. No one moves. I can see the fear on their faces. Cowards.

Roddy looks at me and sighs. “Your father would have gotten us all killed, you included. I’m going to save your life. Hate me now, but you’ll thank me later.”

“You’re not saving my life. I’m already dying. There’s a cure, and my father knew how to find it.”

No one stirs, but the shame on every face deepens.

I look at the star and find it ahead of us. “What are you doing? The star should be on our left.”

“I’m going this way now.”

“But you can’t. As long as we’re still in the fog, we have to keep the star to our left. It’s the only way.”

“And yet, here we go this way.”

I look to the others, but they may as well be catatonic. I see them sneak looks at one another, but they quickly avert their eyes and look downward. They let Roddy kill my father and did nothing. Now they let the murderer take charge of the boat and are too afraid to stop him, though there are four of them—five of us—to one Roddy.

I stare at Roddy’s eyes. I want him to know I’m not afraid. He glances at me but quickly looks away. He rows silently, his face trying hard to look grim and determined, but once I stare long enough, I can see the doubt.